Have you heard the term “patent medicine”? This term first appeared in England during the early 1700’s to identify medications created for the royal family. These medications were awarded “patents of royal favor” to promote their quality. In the United States although similar medications were not regulated or patented by the government, the name “patent medication” was still used. During the 19th century, the cost of seeing a physician was more than many people could afford. Additionally, many feared the typical treatments provided by physicians of that time. Patent medication manufacturer's jumped on the chance to provide alternative treatments for the American public. To sell their goods, these manufacturer's developed advertisements based upon bold claims and flashy appeal. Drug makers used bright colors, creative language, and eye-catching designs to convince the public to buy, buy, buy!

Typically, it was claimed that these medications contained some particularly effective secret or unusual ingredient. Perhaps it was a rare herb only known to Native Americans, or a highly-purified component produced in a state-of-the-art laboratory. Many patent medications were claimed to be “cure-all's” or to cure multiple illnesses. However, in reality most of these medications contained nothing more than common substances such as alcohol, herbs, and plant oils. Some even contained ingredients we now know to be harmful, such as mercury, opium, or even cocaine!

Medication Advertising in History: Convincing the Public to Purchase

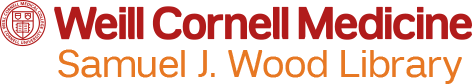

Before television and the internet, medication manufacturers needed to advertise their medicines through other methods. Beginning around the mid-1800’s, traveling salesmen would set up stands in town squares or in the back of their horse-drawn wagons to sell their “patent medicines”, claiming they to cure illnesses ranging from headaches to “feminine weakness.” Known as Traveling Medicine Shows, local residents would gather around the salesman and listen their pitch, which might include songs or short skits. These events were created to entertain viewers in hopes that they would listen longer and ultimately end up buying the salesman's products.

Salesman speaks to crowd during a Traveling Medicine Show in Huntingdon, Tennessee (1944). Source: https://loc.getarchive.net/topics/medicine+show

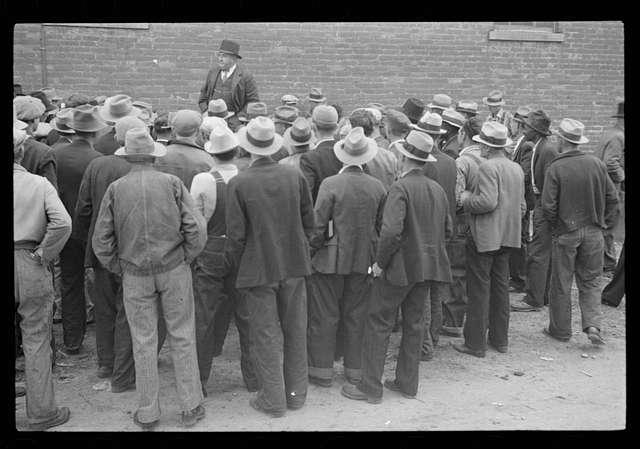

Around this same time-period, another method of advertising was also becoming more popular. Small paper cards (around 3x5 inches), known as "trade cards", were created to advertise patent medications, as well as clothing, food, and cosmetics. They were available from salesmen, at local pharmacies and general stores, or through the mail. Unlike traditional newspaper advertisements, trade cards were an innovation in advertisement due to their use of vibrant colors, the unrestricted variety of products promoted, and ease at which they were circulated to the public. They were often printed in color and were made to be highly collectable (Hale, 2000). In fact, by the turn-of-the-20th century, it was common for people to create scrapbooks to store and display the trade cards they had collected.

Ayer's Cathartic Pills Medical Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.24754685

One of the reasons that trade cards were so common was that they could be easily produced. During the first half of the 1800’s, a new method of printing known as lithography had been developed in Europe. This process enabled artists to create colorful images which could be easily transferred to paper. At first hand-powered, by the mid-1800's American printers had developed steam-powered lithographic presses that dramatically sped up the process. American companies turned to this improved technology to quickly create cheap, visually pleasing pieces of advertising (Marzio, 1971).

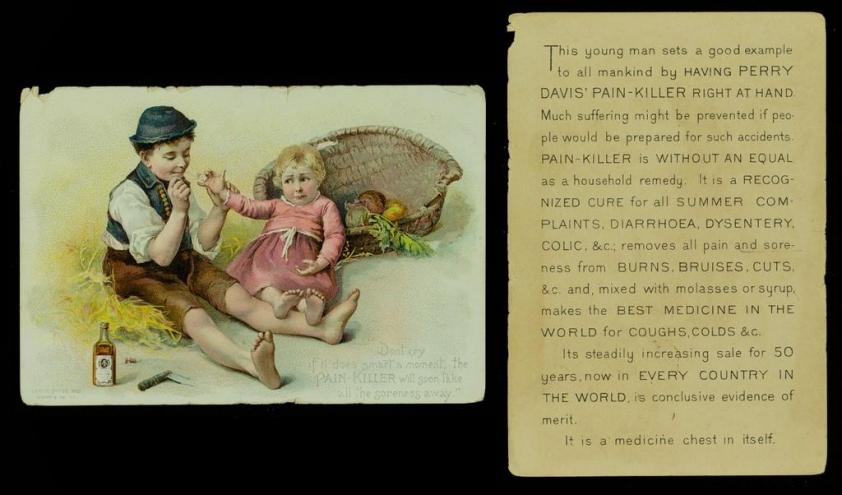

Key to their appeal, medical trade cards often contained imagery that was meant to connect with contemporary consumer tastes, such as flower bouquets, rosy-cheeked children, and animals. Unfortunately, some trade cards and other advertisements also depicted and perpetuated bias against women, as well as negative racial and ethnic stereotypes.

![]() IMPORTANT!

IMPORTANT!

These types of unregulated and unproven patent medications are sometimes called “snake oil”. The people that sold these products to get rich are sometimes referred to as "snake oil salesmen”. This phrase actually comes from a popular patent medicine from the 1800’s known as Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment. This product claimed that it included actual oil from snakes, reducing pain and inflammation if rubbed on the skin. In 1916, this medication was tested by the United States government's Bureau of Chemistry (now known as the Food and Drug Administration or FDA). It was found to contain mostly mineral oil, along with a small amount of beef oil, capsaicin from chili peppers, turpentine, and camphor. Findings such as this alerted the public that sometimes they could not always trust what they saw advertised!

Take a Look!

Assessing: Images, Text and Claims

Medication Trade Card Images

Overall, when the medical trade cards held by Weill Cornell were examined, several visual themes emerged. Healthy, happy babies and small children were often featured. The children featured were often girls, usually Caucasian and blonde. At times they were seen playing with other children, at other times they were alone looking quietly at the viewer. It seems as if many of these images were meant to evoke a feeling of innocence, and to help the viewer recall the energy or optimism of youth.

Tarrant's Seltzer Aperient Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28314956

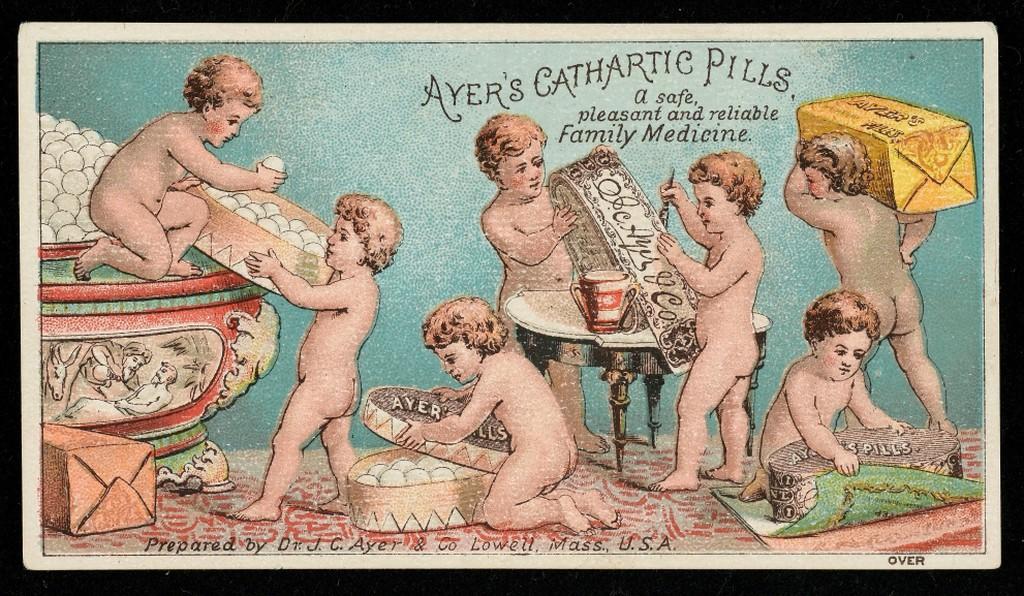

Aside from children, women were also frequently depicted. Sometimes they appeared alongside children, holding them in well-appointed houses or outside in green gardens. Other times women were shown holding striking poses wearing colorful, eye-catching clothes. As with the children depicted in these early advertisements, the women shown were overwhelmingly Caucasian, although most were depicted with brown (instead of blonde) hair. Shown as they were, these women provide viewers with images of comfort and beauty.

Animals were also commonly featured on these medical trade cards. Cats and kittens were some of the most prevalent animals shown. But birds, dogs, and horses were also depicted with regularity. When animals were included, they often were depicted in humors scenes meant to draw the viewer in to more closely connect with the medication advertised. Other times they were included to add a sense of realism and provide a calming glimpse of the countryside.

These visual themes of energy, hope, comfort, beauty, and calmness were some of the most prevalent seen among the advertising images from Weill Cornell’s Trade Card Collection.

These were the sentiments that the manufactures of these patent medications wanted viewers to feel. By connecting their products to these pleasant images and emotions, these manufacturers wanted the public to see their products as desirable, as something to be purchased. Aside from using images to sell products, they were also used to entice people to collect and save trade cards. As women and children were the groups that most often collected these cards, historians have noted that their illustrations were created to most directly appeal to these individuals.

Hall's Vegetable Sicilian Hair Renewer Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28285294.

It is important to take some time to discuss what wasn’t seen among these images. Missing among these were comparable images of people of color. While Caucasian individuals were often depicted in scenes meant to evoke hope, comfort, and health. People of color, in the rare cases when they were depicted, appeared as stereotypes or in racially insensitive troupes meant to evoke laughter, or to highlight the exotic, rare nature of a particular culture. Historians have pointed out the problematic nature of these types of images, as they present non-white individuals as “others”, and not seen as full-fledged members of turn-of-the-19th-century society (Marcellus, 2008).

Text and Medical Trade Card Claims

Aside from images, pharmaceutical manufacturers sought to influence people to buy their products though convincing product claims, written endorsements, and catchy slogans.

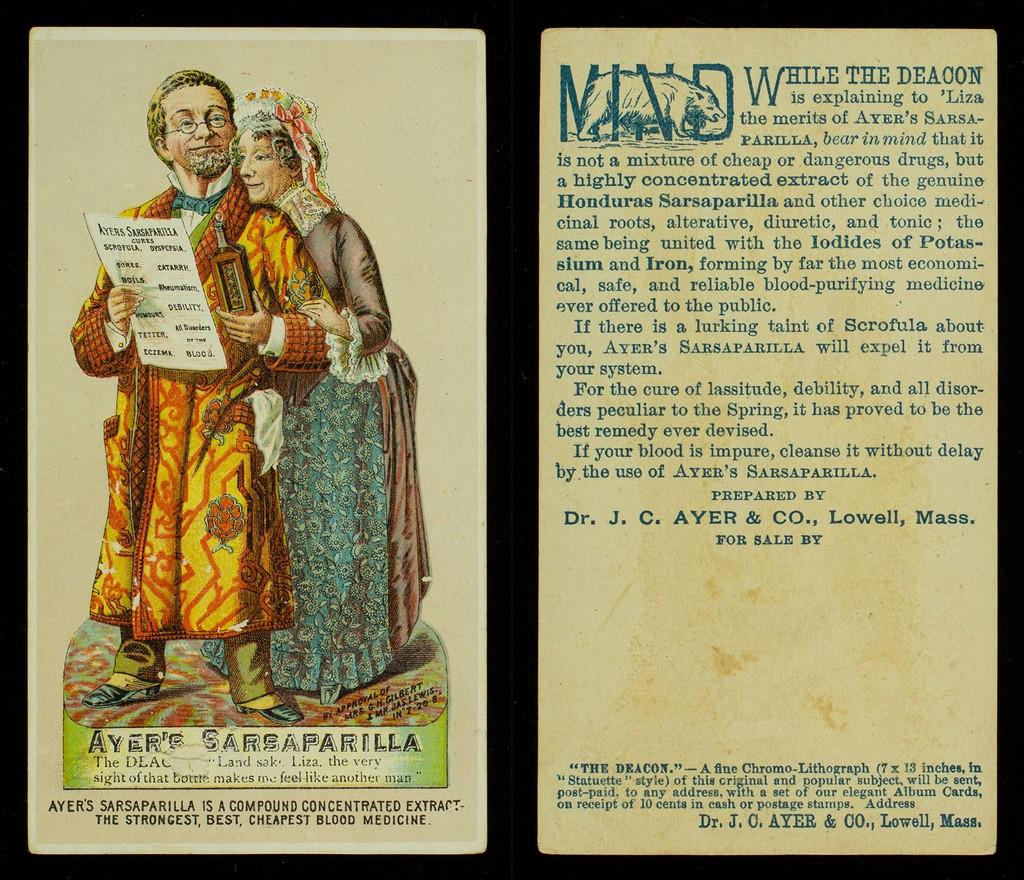

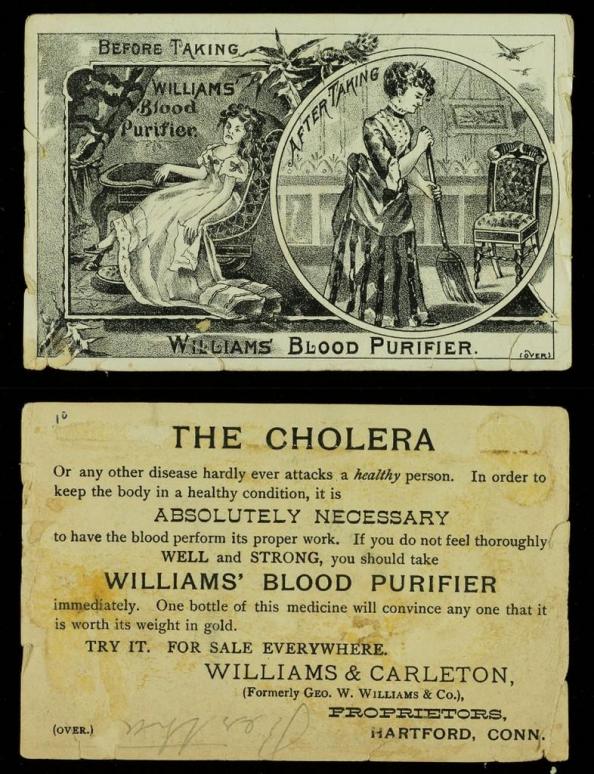

Unsurprisingly, product claims were one of the most common written features of trade cards. These claims were meant to introduce potential customers to the uses of the medication advertised. Often, medications were advertised to have treated multiple illnesses. For example, one famous patent medication Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound advertised 22 different uses including “ovarian troubles... spinal weakness... tumors form the uterus... indigestion... and kidney complaints”. To further convince people to purchase their products, trade cards also promoted their product as overwhelmingly appealing - they were the “most effective”, “extremely popular”, “time-tested”, “economical”, “a natural wonder”, or “a scientific marvel”. Together, these claims appealed to specific sides of public sentiment, to convince the general public as to the usefulness and appropriateness of the medication advertised.

Endorsements were also commonly used. When looking at the people who endorsed patent medications, they tended to fall into two categories:

1) health professionals such as physicians and pharmacists who recommended these medications to their patients

2) patients who used these medications to regain their health. These patients tended to be either accomplished men such as judges, ministers, and artists, or long-suffering women.

Note that in these endorsements, when a man’s words were included their status as a professional was stressed. Even when they were a patient, their endorsements spoke of how a medication helped them return to work. When a women’s words were used, they often reported extensive suffering or frequent bouts of illness. In this way, these endorsements reinforced stereotypes prevalent during the turn-of-the-19th-Century: men were meant to been seen as intellectual providers, and women were naturally weaker.

Dr. Thomas' Eclectric Oil Trade Card Detail (Verso). Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28282067

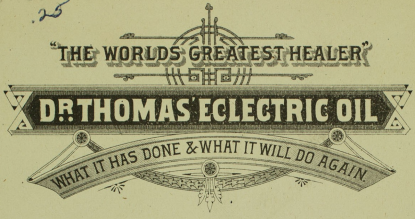

Slogans were also used to connect with customers. Pond’s Extract for example urged the public to “Never Abandon Old Friends” withone slogan, and remined them that it was “The People's Remedy...” in another. Using slogans like these, Pond’s worked to convince the public of its product’s time-honored usefulness, as a product ready to help everyone. Another product, Dr. Thomas' Eclectric Oil advertised itself though the slogan “The World’s Greatest Healer”. With this simple slogan, Dr. Thomas’s oil positioned itself as a tremendously popular, effective source of hope and health.

By taking the time to more thoroughly study the images and statements found on these historic trade cards, we can glimpse into the culture of the 1800’s. We can learn more about the illnesses these individuals were suffering from, as well as how medication manufacturers sought to convince the public of their product’s necessity. Studying these trade cards also provides important evidence as to how medication advertising has developed and evolved, though how the attempts to influence consumer interests has remained the same.

Activity Time!

Closely observe the front and back of the three selected medical trade cards below. Use the following questions to help you evalaute both the visual and the textual messages featured in each advertsment.

Look at the Images (Front of the Card):

Where is your eye drawn first?

What parts of these images capture your attention?

How do you feel looking at this image?

What do you feel about the medication when looking at the image?

What components of the image are working to convince you to buy this product?

Look at the Text (Back of the Card):

What is the product advertised to treat?

What words or slogans catch your attention?

How does the information supplied make you feel about the advertised product?

Look for any patient or health care provider endorsements - are there any included?

When looking at the back of the trade card, what else is working to convince you to buy this product?

Example 1: Ayer’s Sarsaparilla Medical Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28280832

Example 2: Williams’ Blood Purifier Medical Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine; https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28315044

Example 3: Perry Davis’ Pain-Killer Medical Trade Card. Source: Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine; https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28305444

To print and complete this activity offline - download the attached worksheet featuring these images and questions:  here!

here!

Where Are They Now: What Happened to Medical Trade Cards?

As the 20th century dawned, trade cards became less common. Part of this is attributed to changing tastes among the general public. Collecting trade cards fell out of fashion. As less people picked these advertisements up from local stores, manufacturers began increasing their advertisements within newspapers, magazines, and on billboards. In 1913, the radio was invented and soon advertising had a new method of connecting with the public.

Still, some of the innovations first seen in trade cards continued to be used in these new kinds of ads. This includes the use of catchy slogans, building of brand appeal, and showing images of what advertisers and manufacturers considered to be happy, healthy people.

Today, medical trade cards can be found in archives, museums, and special collection libraries. They are often digitized by these organizations and made available online due to their visual appeal.

The Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine preserves 197 colorful trade cards promoting nineteenth-century medical services and products. The advertisements in this collection claim to cure a variety of ailments from the common cold to balding. Click here to view the entire collection!

Want to learn more about medical trade cards? You can check out additional trade card collections hosted by other institutions in our About Us section!

Click here for information on authors and works cited.